9 Bubbles

On 10 March 1999, the technology firm-rich NASDAQ composite index closed at 2,406. On 10 March 2000, it had more than doubled to 5,048. By 9 October 2002 however, the index had crashed to 1,114.

It is commonly argued that the pricing of these firms comprising the NASDAQ was irrational or a “bubble”. Bubbles are said to exist when prices are far above an intrinsic value based on fundamentals.

There is a large academic debate about what comprises a bubble. Do bubbles exist? Can a bubble be identified before a crash?

However, lab experiments provide a compelling case that, when many of the possible rational explanations for very high prices are eliminated through the experiment design, that bubbles do exist.

9.1 An experimental bubble

The first paper to explore bubbles in an experimental asset market was by Smith et al. (1988). This has now led to a large literature on the topic.

A typical bubble experiment involves an asset that is to be traded over a fixed number of periods. The asset pays a dividend on a known schedule and known probability distribution. This allows traders to calculate the fundamental value easily at any time.

As an example from one experiment by Ackert et al. (2006), each trader was given two shares of an asset that each period paid a dividend of $0.50 with probability 48%, $0.90 with probability 48% and $1.20 with probability 4%. The expected value of the dividend in each period was:

0.48*\$0.50 + 0.48*\$0.90 + 0.04*\$1.20 = \$0.72

As the experiment ran for 12 period, the expected value of the asset in period 1 was $8.64. To calculate the expected value at any time, multiply $0.72 by the number of remaining periods.

For a risk neutral trader, this expected value is the fundamental value of the asset. For a risk averse person, the fundamental value would be lower as they must be compensated for the risk.

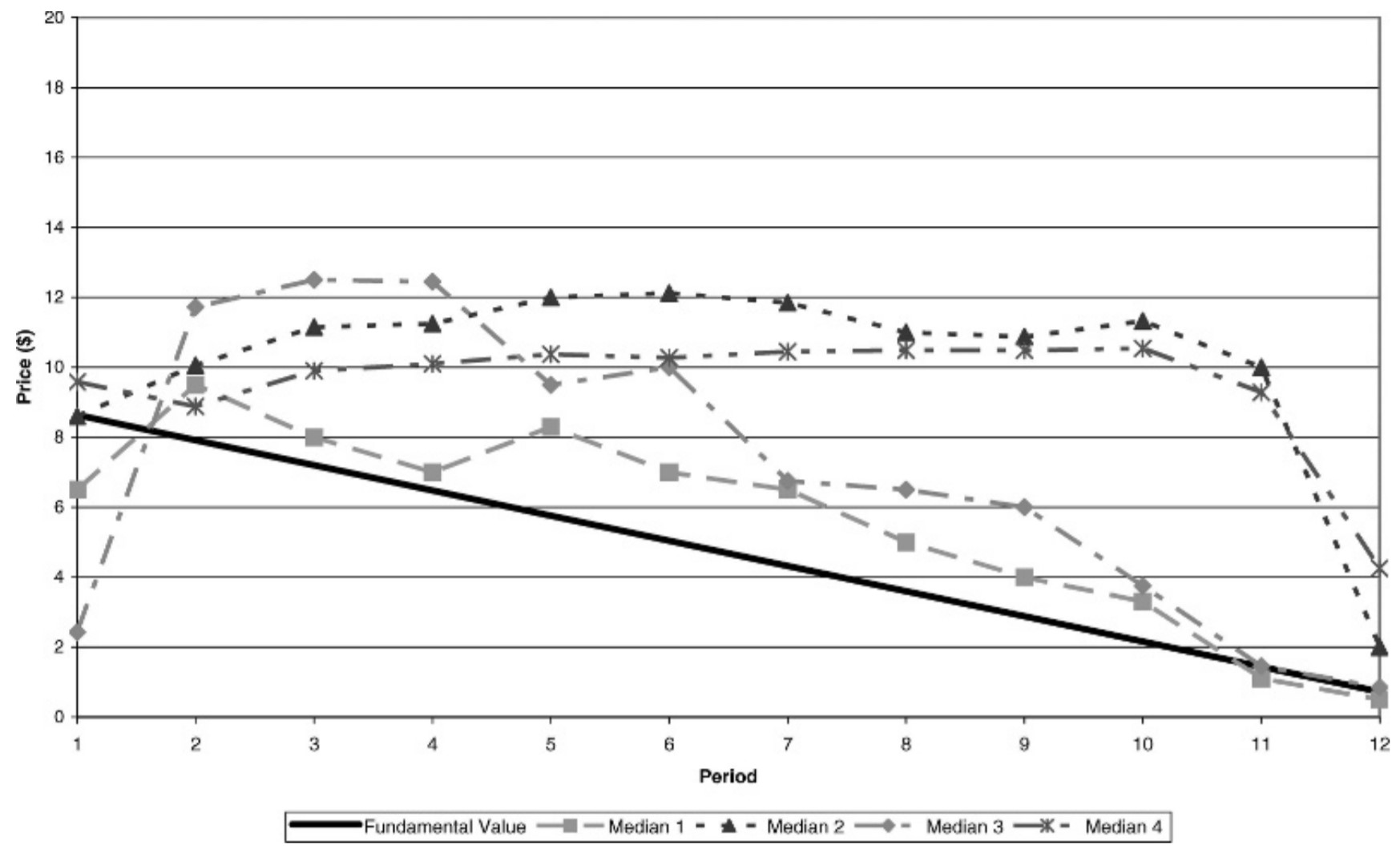

In the Ackert and friends experiment there was five minutes of trading using a computerised platform before each dividend payment. A plot of the price in four markets over the 12 periods, plus the fundamental value, is shown below.

This price pattern is typical of that in experimental bubble markets. Although the price is below fundamental value in two of the markets in the first period, it quickly rises above the fundamental value. Often the bubbles are persistent - as are two here - before finally crashing just before the music stops.

Importantly, these bubble are created despite the intrinsic value of the security being trivial to calculate at any point of time. That, of course, is not the case in a real market. But the fact bubbles can occur when the value is obvious suggests that uncertainty cannot be a complete explanation for their emergence.

Although not explored in the papers noted above, one other themes that has emerged from these experiments is that with experienced traders or bubble market experimental participants, the bubbles are milder and disappear earlier.